Excerpt: A Classic Novel of the Nazis’ Rise That Holds Lessons for Today

Lion Feuchtwanger’s 1933 novel “The Oppermanns,” newly reissued, raises salient questions about the relationship between art and politics.

By Joshua Cohen

Originally published in The New York Times

There is a famous saying in Talmud, attributed to the sage Tarfon: “It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you free to neglect it.” For Tarfon, “the work” was the study of Torah — that is, the unfinishable task of trying to understand God’s word. But with the gradual and tenuous emancipations of European Jewry throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Tarfon’s injunction to study became assimilated too, as Jews were admitted to secular schools and exchanged the traditional texts for the sciences. In effect, the task stayed the same, while “the work” itself changed, from the study of God’s word to the study of (for example) medicine and law. For German Jews in particular, “the work” came to stand for the free transmission of knowledge, the assertion of moral absolutes and ethical standards, and the preservation of the Enlightenment-era democratic rationality that had finally liberated them from the ghettos in the revolutions of 1848, and that would keep them out of the ghettos for just under a century.

One of the last masterpieces of German Jewish culture, Lion Feuchtwanger’s 1933 novel “The Oppermanns,” offers its own version of Tarfon: “It is upon us to begin the work. It is not upon us to complete it.” Superficially, “The Oppermanns” is a novel about the decline and fall of a bourgeois German Jewish furniture dynasty whose members are unable to countenance the rising threat of National Socialism. It is also, in a way, a novel about this phrase, which recurs in its pages like a psychological test or a trial of identity.

The phrase first appears on a postcard written by the hero of this novel, Gustav Oppermann, to himself on his 50th birthday; “the work” he’s referring to is the biography he is attempting to write of the German philosopher and dramatist Gotthold Lessing. Later, as a refugee in Switzerland, Gustav finds the unsent postcard mixed up with a bundle of smuggled documents detailing Nazi atrocities. This is where “the work” becomes political: an exhortation to parse truth from lie and publicize the evil. Next, the phrase occurs to Gustav on the shores of Lake Lugano, where the Oppermann family has gathered to hold a final Passover: “The work” is now the perpetuation of Jewishness in the face of an enemy even crueler than Pharaoh. We meet the phrase one last time, when Gustav — having survived capture by the Nazis and a stint in a forced labor camp — has the postcard sent to his nephew, who has escaped to England. For the younger generation, Feuchtwanger implies, “the work” must mean something else again, perhaps the work of self-reinvention, perhaps the work of healing.

“The Oppermanns” challenges its characters, and by extension its readers, to redefine “the work” again and again: Is it Werk, which is work in the sense of an artwork, the product of mental and spiritual labor? Or is it Arbeit, work in the sense of effort or labor, the hard physical exertion that, as the gates of Auschwitz remind us, “makes us free”? Feuchtwanger’s translation of Tarfon, “am Werke zu arbeiten,” literally means “to work at the work,” but the worlds of those words are in conflict, and it’s this conflict that’s fundamental: the conflict between the aesthetic work of art and the activist work of politics, between reading in comfort and going into the streets to foment a revolution. “The Oppermanns” immerses us in these oppositions, and in our own contradictions, and reminds us, every time we leave the page to check our phones, that just reading a novel about the German 1930s — about pervasive surveillance and militarized policing, about how the fake-news threats of “migrants” and “terrorism” can be manipulated to crush democratic norms — will never be enough to prevent any of that from ever happening again.

A Nazi book burning in 1933 consigned some of Feuchtwanger’s work to the flames, along with books by Sigmund Freud, Erich Kästner and others. © dpa/picture alliance via Getty Images

Feuchtwanger’s Oppermanns are a family “established in Germany from time immemorial.” Immanuel Oppermann, a merchant, was the first of the family to come to Berlin; he supplied the Prussian Army and founded the furniture firm that bears his name. The novel’s principal characters are Immanuel’s grandchildren, who with their own children make up a refined cast that would formerly have filled a long and leisurely family-saga-as-national-epic-type-novel like “Buddenbrooks” or one of Tolstoy’s glorious doorstops. Instead, the Oppermanns were the creation of an author on the run — short on time, short on paper and ink, short on everything but purpose. In the nine months between the spring and the fall of 1933, he conjured an entire world and chronicled its destruction, which he set within another nine-month span, more-or-less simultaneous — specifically, between the last free elections of the Weimar Republic in winter 1932 and Hitler’s outlawing of non-Nazi parties and dissolution of the Reichstag in summer 1933.

In other words, Feuchtwanger wrote “The Oppermanns” in real time, as the events he was writing about were still unfolding, and even while he was suffering the same tragedies as his characters: In 1933, his property in Berlin was seized; his books were purged from German libraries and burned; he was banned from publishing in the Reich; and he was stripped of his German citizenship.

As the book’s quick-cuts and montage sequences might suggest, “The Oppermanns” was initially conceived for the screen. But when the deal fell through, an enraged Feuchtwanger (now living stateless in exile on the Provençal coast) set about transforming the material into a novel. Drawing on the daily headlines, firsthand information from journalist friends in Germany and contraband reports of Nazi violence, Feuchtwanger finished the novel by October 1933; a U.S. edition appeared a few months later. On its original publication, “The Oppermanns” sold approximately 20,000 copies in German, was translated into 10 other languages besides English, and sold an estimated quarter-million copies worldwide — yet it did nothing to alter the appeasement policies of Britain’s prewar prime ministers, and it certainly didn’t get the United States to reconsider its doctrine of isolationism.

Lion Feuchtwanger wrote “The Oppermanns” in real time, as the events he was writing about were still unfolding, and even while he was suffering the same tragedies as his characters. © The New York Times

Given that Feuchtwanger’s books were so explicitly and accessibly addressed to a general audience, it’s poignant that he has none now. His novels go unread; his plays go unperformed; he’s a first-class writer without a first-class berth; a classic firebrand without a canon. Most of his work was clearly meant as a commentary on the Weimar Republic, yet America — where he eventually settled and became an eminence of the émigré circuit — proved singularly unreceptive to the socialist-realist principle that art can have a message; and that such art-with-a-message, which will always be dismissed as propaganda, is in fact the only available corrective to the real and actual propaganda of entrenched power.

Feuchtwanger expected his work not just to be something, but to do something: the Werk giving rise to Arbeit, which can bring about a change. But the German-language novelists of his era whose reputations have survived were of another mind entirely. They didn’t think their novels should do anything; their novels were just novels, objects entombing subjectivity and all that it entails, including political agendas.

Under the Trump presidency, many would-be Cassandras quoted (and misquoted) the dead Germans and German Jews of Weimar; many warned of a Weimar sequel occurring here at home. There was a new call for clarity in the arts — a call for the arts to provide the humane leadership that government lacked, and to spark a national reckoning with identity and inequality. For the first time since Vietnam, young American writers have felt compelled to provide a literature of protest, one that demands not just to be read but to be acted upon, and to be judged less on aesthetic grounds than by the urgency of its convictions.

Feuchtwanger’s life, and his afterlife, provide cautionary lessons for these writers of the left. His example shows that art can challenge power, as it were, “powerfully,” and yet have no political effect. Still, “The Oppermanns” also shows that a work intended to sound an alarm can echo beyond its emergency, if written with honest detail, great dramatic skill and a deep feeling for the individual human, whose experience of the news is called “life.”

This is the work, which it is not upon us to complete, only to begin.

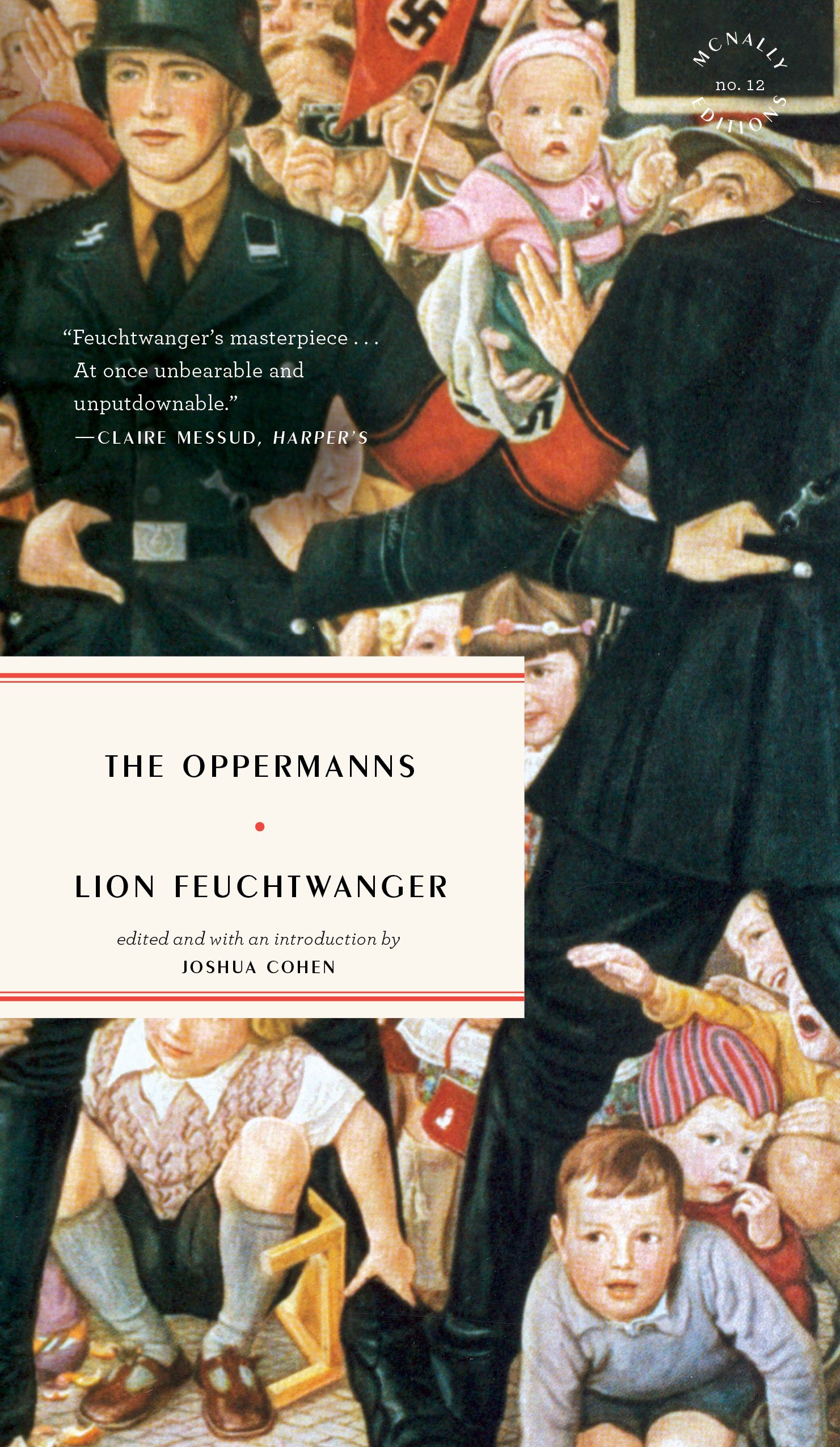

Joshua Cohen won the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction this year for his novel The Netanyahus.” This essay is adapted from his introduction to a new edition of “The Oppermanns,” to be published by McNally Editions this month.