A Survey of McNally Editions, the Boutique Publisher of Out-of-Print Gems - The Seattle Times

By Emma Levy

Originally published in The Seattle Times

The impeccably curated New York bookstore McNally Jackson has launched a publishing arm, McNally Editions, dedicated to resurfacing “hidden gems” and “lost classics.” These are works that have gone out of print or been otherwise neglected by the factory that is book publishing with no reflection on their merit or timeliness. Now they are given a new life.

The Goodby People, by Gavin Lambert

Gavin Lambert made a career of cataloging the lives of Hollywood’s chic and capricious in his novels, biographies, criticism and screenplays. 1971’s The Goodby People takes place in the precise era when Hollywood was exiting its Golden Age, and the city known as Los Angeles was developing an adjacent but not unrelated mythology. This is a city where aging starlets and serious writers mix socially with transients and other “refugees from the planned functional world.”

With the quips of Dorothy Parker and the aloof, surveying eye of Joan Didion, our unnamed narrator — a Lambert doppelgänger — chronicles his experiences with several people that pass in and out his life: a reclusive star, a vain draft dodger and a recent L.A. transplant being haunted by the ghost of a long forgotten leading lady. Like any novelist obsessed with his characters, the narrator is savvy, composed, and for the most part, just lets events unfold around him. He observes “the aura of joylessness which surrounds so many rich, powerful, and clever people” and an actress with a voice “perfectly pitched for lying.” This wry, chatty portrait feels like a vital piece of L.A.’s cultural history, and it deserves to be on display right next to Eve Babitz.

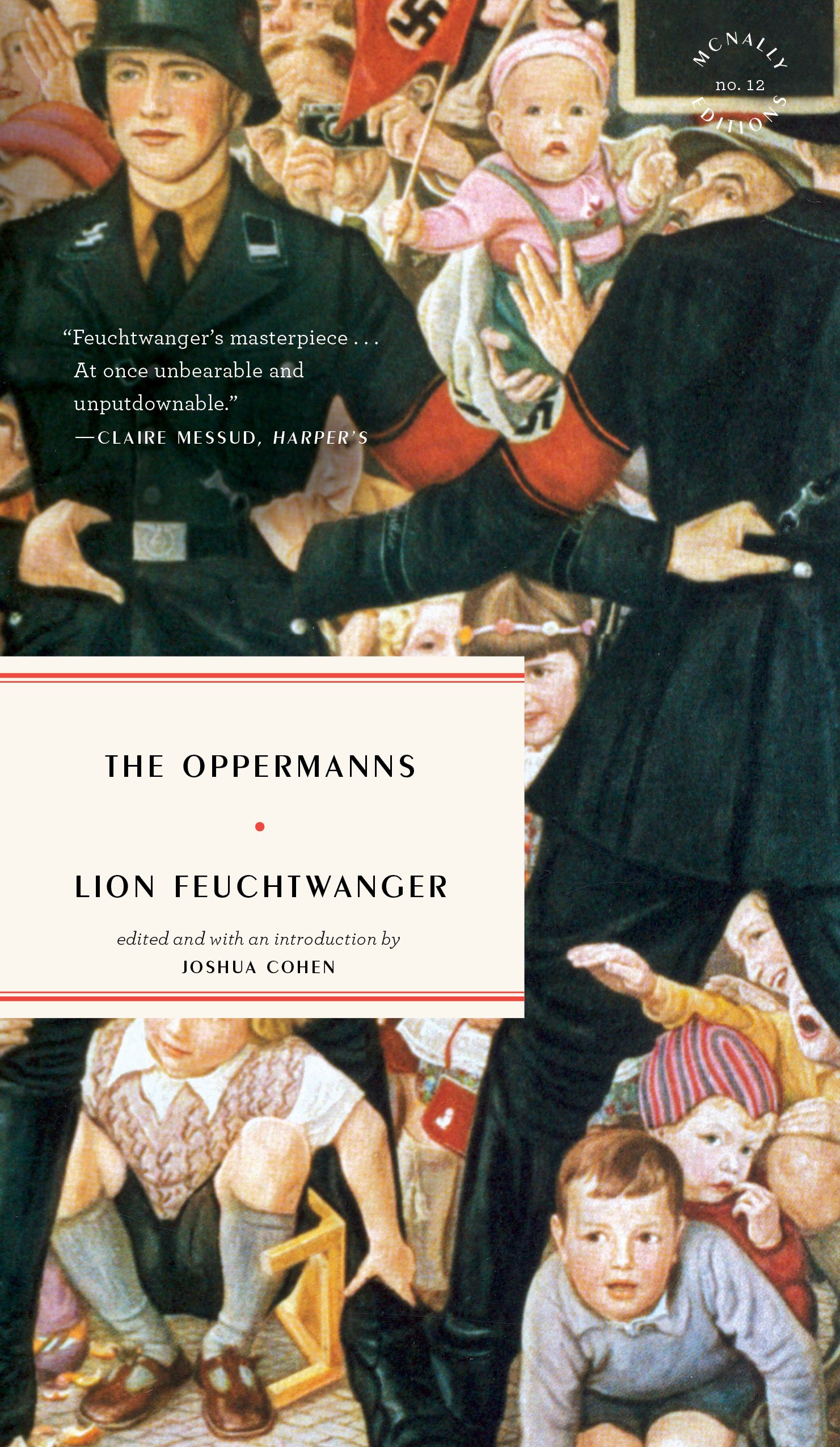

The Oppermanns, by Lion Feuchtwanger

The Pulitzer-winning author Joshua Cohen wrote in his introduction for The Oppermanns that it was “one of the last masterpieces of German Jewish culture.” This characterization may sound interchangeable with the typical phatic praise you’d find in any novel’s introduction if you’re reading somewhat distractedly on an airplane as I initially was, but they are words that chill your blood when you stop to consider that the German Jewish culture from which Lion Feuchtwanger arose was being systemically extinguished in real time as he wrote this novel.

The Oppermanns follows a family with a prosperous furniture business whose very foundation lay in having rendered “good service” to the German army during the Franco-Prussian War; a letter signed by a field marshal declaring so was ceremoniously framed on their office wall. However, their devotion to Germany was no match for the rising tide of nationalism enveloping the country. Gustav, the Oppermann who left the family’s business to study literature, at one point tries to convince his family that despite mounting violence, the German people are fundamentally rational because Goethe’s books had sold a hundred million copies. The genius of The Oppermanns is in its demonstration of how nationalistic mythmaking worked in real time, and how a layered yet full-hearted patriotism was traded for “doglike obedience” and mandatory worship of the country’s founding lore. We are in an era when Holocaust education is at a woeful nadir and those who bore witness will soon no longer be here to remind us of our still-relevant history. We will still have The Oppermanns. This is the power of literature.

Something to Do With Paying Attention, by David Foster Wallace

I’ve been disappointed to see the way David Foster Wallace has become something of a punchline in certain pockets of the internet, especially among people who (just guessing here) have likely never read a page of his work. He can be a challenging writer, prone to long digressions, serial descriptions and elaborate concepts. But if you attune yourself to the rhythms of his sentences, you’ll find that something divine and delicate will emerge.

Something to Do With Paying Attention — the novella conscientiously extracted from Wallace’s unfinished The Pale King — is about boredom, and what can be found within it. The first third is an accounting of details the narrator remembers from growing up in the 1970s: sideburns, wastoids, the word “excellent,” the antique ships on display for the bicentennial, what Tang tasted like when you ate it straight from the container with your finger. Wallace has an eye for Americana: the kitsch, the disorder, the atomization. You soon realize the novel is the origin story of an IRS agent who has found something sacred in the tedium of his work. Through a combination of female-targeted diet drugs used recreationally and a sermon given by a substitute accounting professor, this character has discovered how to hone his attention, how to become vigilant to the cascade of details that actually make up a life.

Wallace is a keen observer of America’s bureaucracies, but he is much more interested in a spiritual critique than a political one. What meaning can an individual find when they dispense with the fantasies of childhood and confront what life is actually like? In a culture profoundly steeped in nihilism and irony, Wallace’s voice is a balm.

Emma Levy: emmalevy30@gmail.com; on Twitter: @emmalev_.