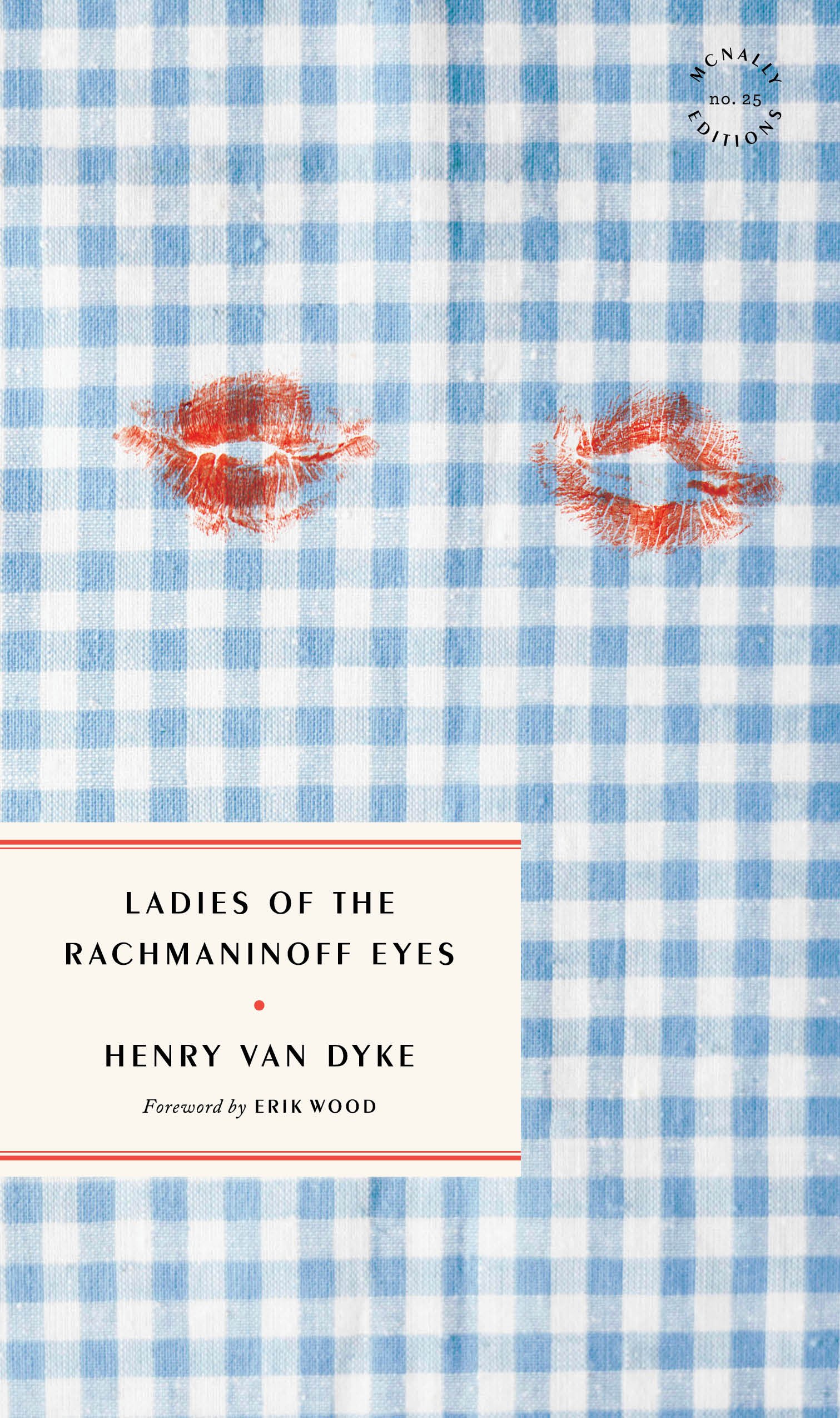

When They Were Pretty: An Excerpt from ‘Ladies of the Rachmaninoff Eyes’

From Ladies of the Rachmaninoff Eyes, which was republished this month by McNally Editions.

By Henry Van Dyke

Originally published in Harper’s

“Heavens, Harriet,” Mrs. Klein said when Aunt Harry gave her the hot rum drink, “I need to send you to bartender’s school. Did you put any rum in it?”

We watched her bend her heavy nose to the brew the second time; only the rain on the bay windows made a sound. Aunt Harry’s face was alert, waiting, under piles of white fiberglass hair. “Well?”

“Slop, Harriet. Absolute slop. Why, I can’t taste a thing but syrup.”

Aunt Harry turned away. “That’s because you’re an alcoholic, that’s why. Rum for breakfast. Rum puddings. Rum salads. How do you expect to taste anything when rum’s the natural state of your taste anyway?”

Mrs. Klein looked at me and tightened her lids in a half wink so all the wrinkles would stand out. “Your aunt’s exaggerating again, dear. She does so like to exaggerate. Don’t you like to exaggerate, Harriet? Harriet? Oh, Harriet, don’t be tedious.”

Aunt Harry placed Dresden china on the table in front of us. “I just said you’re an alcoholic. I stated a fact. That’s all I ever do—state facts.”

A rose tinge came to Mrs. Klein’s chalk in her cheeks. “But, really, now, I don’t drink that much. You think I drink that much, Oliver?”

“If you was to die tomorrow, Etta Klein, they’d be afraid to cremate you with all that alcohol you’ve got in you. You’d start a conflagrating fire.”

“Foot,” Mrs. Klein said, tapping the black satin around her brooch. “Isn’t she a comedian, Oliver, conflagrating, ha! I don’t think she’s funny at all.” Her laugh, with mahogany teeth, was the sound of soft rifle shots, but quickly she stopped it and turned toward Aunt Harry and the silverware. “Anyway, I may not get cremated.”

“You’ll get cremated.”

“Not if I don’t want to.”

“All Jews get cremated, don’t they?”

Mrs. Klein drew out a grand handkerchief of Brussels lace. “Dearest Harriet, you’re so ignorant about Judaism. That’s one area I think you ought to just stay clear out of.”

“Well, I’m only going by what I’ve heard and what I’ve seen. You cremated Sargeant didn’t you? You had your own son cremated. Now just try to tell me that that’s exaggerating.”

Quietly Mrs. Klein looked dead into Aunt Harry’s dark face, dabbing all the while her Brussels lace to her goitered neck. “Sargeant, Mrs. Gibbs, asked to be cremated. He chose to be cremated. Sargeant … Sargeant … ”

I never knew what to do about ladies crying, and at Green Acorns both of them cried usually at the same time or in close sequence. Once, earlier in June, when then they thought Della was made pregnant by a farm equipment salesman from Chicago (she wasn’t; Della lied to soften them up for a raise in salary), they both began to cry—Mrs. Klein in barking, suffering noises, and Aunt Harry in a whinny. I had said, “Stop, Mrs. Klein, it’s all right,” and then I ran over to console Aunt Harry with “Now, now, Auntie, it’s all right,” and then back again to Mrs. Klein. It was a relay race of sorts.

But worse was the aftermath: Mrs. Klein, who apparently needed to pay penitence for an excess of sentiment, chose me to help her expiate her venial weakness: we would dig weeds in the hot sun, or wash PG, the cat. With Aunt Harry the aftermath of a crying spell was less physical but no less painful. Admonitions and sneers came from her pony face, a face chock-full of wrath. “I’m ashamed of you. Sucking up to that white woman just as if she was your dear, dead Mama.” And if I tried to point out that I was consoling both of them, she’d say: “Yeah? But you was with her the most. You suck up to old Mrs. Klein like she was your relative instead of me. Just because she’s sending you to that fancy college to study and you can say a few fancy French words, you think I don’t count for anything, don’t you?”

Oh, I knew their tears would stop; they’d begin with a noisy jolt, just like the shower in the west room, and like the shower their tears would stop without warning. But meanwhile I had to placate such opposite souls with the same words, the same frightened nonsense. And they did frighten me—those ladies with tears coming out of their ancient eyes, those eyes so like old pictures of Rachmaninoff’s eyes. Moreover, their indelicacy frightened me. What was I to do? And now this crying, an indecent duet, was instigated by Aunt Harry’s quip about Sargeant, Mrs. Klein’s bachelor son, who slashed his wrists in New York City, in a Sutton Place bathtub, five New Year’s Eves ago.

Mrs. Klein was smoking an English Oval and reading her horoscope magazine. “At least one thing,” she said, not looking up, “I was true to my Ezra when he was alive, Mrs. Gibbs. That’s more than you can say for yourself, I’ll wager.”

“I never even looked at another man till the day Gideon Gibbs killed hisself by working his fool head off. For what? For the Klein family who didn’t ’preciate him no how. Doubling as chauffeur, yardman, every thingamajig. Lord, it might’ve been the Depression days, but you wasn’t all that depressed. Slave labor. I thought many times of putting the NAACP on the whole lot of you.”

Mrs. Klein frowned at her cigarette; it wasn’t drawing; it was unlit. “Oh, hush, Harriet, you don’t even know what the NAACP is.”

(I never knew how much of the fight between the two ladies was real, how much was diabolical jest, how much was hate, how much was love.)

“Listen, Oliver,” Aunt Harry said, “just to show you how cheap the Kleins were in those days—listen. Your great-uncle Gideon Gibbs worked like a slave. He drove that silly old limousine of theirs. He loved that car. But you think they ’preciated that? They—”

“Harriet! Now, you needn’t go into—”

“They wouldn’t even buy him a chauffeur’s uniform—until one day! Oh, Lord, I think I’ll never forget that day! One day Gideon drove Etta downtown to pick up some visiting business gentlemen of Mr. Klein’s. This is hysterical. One day—”

“Now, Harriet, I don’t think it’s necessary that Oliver know this. It was a long time ago, for heaven’s sake.”

Aunt Harry’s eyes were cat glints, gleaming like PG’s do on her evil days. “First of all, your great-uncle Gideon was very light-skinned. You seen pictures of him on my bureau.”

“Really, Harriet, can’t you talk without jiggling the coffee all over the place?”

“Anyway, Oliver, Gideon was white as a colored man could get without being actually white. So, these cheap Kleins in 1934 asked Gideon to buy his own chauffeur’s uniform. Course Gideon wouldn’t. He was too principled, Gideon was. And he was neat. I pressed his best suit—and that cost us, too, I’ll have you know—and he wore it with a white shirt and a tie. Then this day comes. Etta went to downtown Kalamazoo and picked up her husband’s—God rest Ezra Klein—business gentlemen. And when they got in the car—you know what? You know what one of them said? One of them said, ‘You sure do keep a fine-looking car, E. J.’ He said this to Gideon. All of them, Gideon told me, practically had hemorrhages right there in the car seat.”

“Harriet!”

“Well? Is it true or isn’t it true? Come on, now, tell Oliver if it’s true or not.”

“Yes, it’s true, but it was an understandable mis—”

“So, sweetie, can you guess what old E. J. Klein and Etta did the very next day? They went right in their so-called depressed pockets and bought your great-uncle Gideon a uniform! Isn’t that right, Etta?”

“Oh, for God’s sake, Harriet, yes, that’s right.”

Della came into the room, her maid’s cap thumbprinted, her dress too tight. Della was twenty-eight and liked men very much. She said she was from Trinidad; Aunt Harry said Georgia. “Will you be having ginger cookies, Mrs. Gibbs?”

Mrs. Klein said, “Must we?”

“Yes, we must, you know very well we must,” said Aunt Harry.

“I hate the very thought of those ghastly ginger things,” Mrs. Klein said. “So—so homey.”

“Everything is homey at Green Acorns.”

Mrs. Klein’s satin frock seemed cold and its black sheen caught in her white hair for moments at a time. A dull brooch on her flat bosom looked at me, and sometimes her blue eyes looked at me too. But she was thinking of—of what? Of Sargeant?

I cleared my throat and smiled, but she would not refocus her gaze. Aunt Harry was foolishly polishing the tea server, as though she hadn’t just polished it last Saturday with the same vigor.

“Are you sad?” I asked. “Does the rain make you sad? You look sad.”

Mrs. Klein turned to the window, touching the brooch at her bosom with the forefingers of each hand. “Why, why, no, Oliver, I was just thinking how beautiful I was once.”

Why I thought this a cue to laugh I don’t know, but I did, falsely, with no cooperation from anyone.

Mrs. Klein woke up. “I was!”

“She sure was, Oliver.” Aunt Harry’s eyes were full of dark fires. “She was a tiny thing. A real beauty.”

I hadn’t really wanted to laugh. “Were you—were you living in Kalamazoo then? When you were pretty, I mean?”

“There. Oh, yes, there. And Long Island for many years. I think that’s when Sargeant got New York in his blood. You know he loved the elevated train more than any single—Oh, yes! Harriet, do you remember that awful row I had with Ezra?”

“Which one, dear?” Aunt Harry was sitting beside Mrs. Klein, practically holding her hand. It was too dizzying, this sudden pro–Mrs. Klein spirit; I simply could not decipher their game: at this moment these ladies were in love.

“You remember.” Mrs. Klein laughed, barked, and moisture came to her eyes. “The time I rode in the car with no clothes on to bitch him.”

They hugged! They snickered! Mrs. Klein’s black satin arms were around Aunt Harry, and Aunt Harry’s green cotton arms were around Mrs. Klein. They giggled and I could hear Della’s tea water hissing through the rain.

“You tell him,” Mrs. Klein said.

“No, no, I couldn’t.”

“You remember.”

Aunt Harry shook her fiberglass head and wiped tears from her eyes. “Oliver wouldn’t understand anyway. It’s not funny to tell. You tell him.”

“Well, get together on it and tell. You were nude in a car, Mrs. Klein?”

She blew her nose and lit an English Oval. “It was in the Thirties. You weren’t even born. Mr. Klein and I had an awful row over some—some nonsense. You know, Harriet, I can’t really remember—really clearly—what the whole thing was about … Oh, Harriet, I can’t, I simply can’t.”

Aunt Harry dug her hard brown fingers into Mrs. Klein’s chubby pink wrists and shook her face with a strange mirth, as though the Holy Ghost had touched her.

“I was young,” Mrs. Klein whispered. “And silly. And so full of living.”

“And you were beautiful.”

“Yes, I suppose. I was beautiful, wasn’t I?”

It stopped raining. Della was whistling How long, how long, have that evenin’ train been gone, and my ladies of the Rachmaninoff eyes were reminiscing, in their widowhood, beyond my reach.