Image 1 of 1

Image 1 of 1

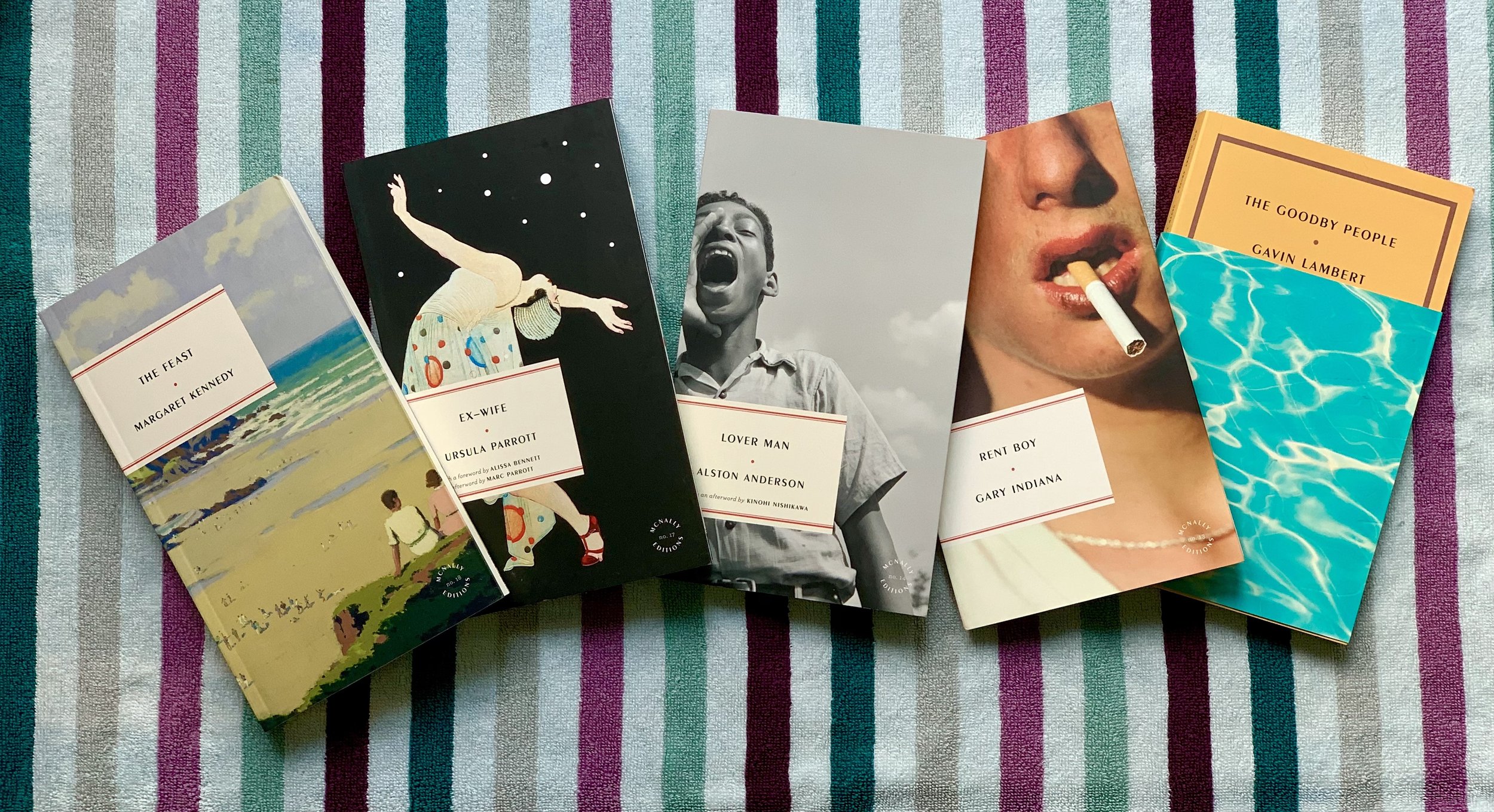

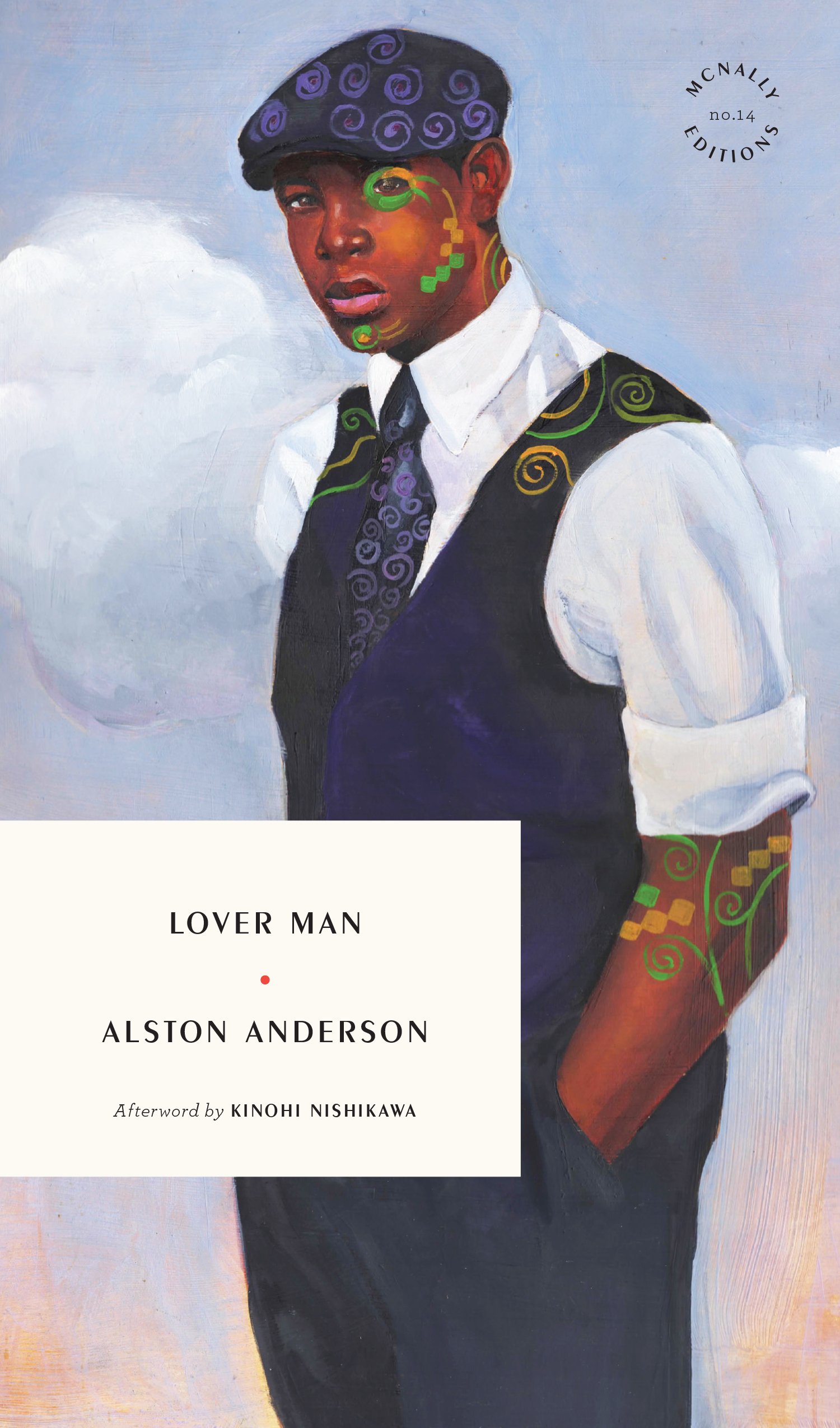

Lover Man

Alston Anderson

Afterword by Kinohi Nishikawa

A classic of 1950s Black fiction: stories of loners, outsiders, tricksters, addicts, jazzmen, and drifters in the Jim Crow South by “a writer with a perfect ear, a warm heart, and an amazing capacity to seize character and make it live” (Selden Rodman, The New York Times)

Alston Anderson

Afterword by Kinohi Nishikawa

A classic of 1950s Black fiction: stories of loners, outsiders, tricksters, addicts, jazzmen, and drifters in the Jim Crow South by “a writer with a perfect ear, a warm heart, and an amazing capacity to seize character and make it live” (Selden Rodman, The New York Times)

The stories in Lover Man (1958) promised the birth of a new sensibility in American fiction. Inspired by the bebop he loved, and the philosophy he studied at the Sorbonne, Alston Anderson looked back at the North Carolina of his youth to capture the hidden lives of Black boys and men in the early ’40s. His male protagonists are loners or outsiders: tricksters, addicts, jazzmen, drifters, queers. His women are also nonconformists, insisting on their own desires rather than capitulate to male fantasies. For Anderson the stakes of individual freedom are high, and Lover Man dramatizes that eternal conflict. It is a series of portraits of struggle: people trapped in myths of white supremacy and male dominance, maddened by the absurdity of a violent, segregated world.

As Kinohi Nishikawa writes in his afterword to this new edition, Anderson’s independence came at a price, since the “queer elements” of his stories offended many contemporary critics. Although they were later championed by Langston Hughes and Henry Louis Gates, among others, this—his only collection—has remained out of print since its debut.

“A gem of Americana . . . These stories span the early decades of the 20th century and address with nuance the Black characters’ negotiations with youthful turmoil, sexual desire, and race in the U.S. . . . Anderson’s feat is in finding the poetry of everyday moments among marginalized people. This deserves a place on the shelf of mid-century classics.”

—Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

“Models of subtlety and sparsity . . . Anderson’s short story ‘Signifying’ is a masterpiece of the genre.”

—Henry Louis Gates

“One of the lost names of Black literature . . . His style is straightforward, but the simplicity is deceptive, the calm surface at odds with the depths sending up their clues . . . His ear, like Hurston’s, can be faultless . . . Lover Man has considerable interest as a portrait of black postwar migration from the lusty, incestuous-feeling, small-town South to the war-changed streets of Harlem . . . His storytelling gifts were undeniable.”

—Darryl Pinckney, The New York Review of Books

“[An] extraordinarily fine first collection . . . [A] writer with a perfect ear, a warm heart, and an amazing capacity to seize character and make it live . . . This reviewer was ensnared by the very first story, a combination of compassion, naturalness and humor. In only one (‘Suzie Q.’) do the dialect and malapropisms seem introduced deliberately for laughs—but you laugh. I had a feeling throughout, as I've had with some of the best West Indian and African writers, that if the novel is ever to come to life again it’s going to start at this level where folk wisdom has not been forgotten, true innocence still exists, characters act as well as feel.”

—Selden Rodman, The New York Times (1959)

“A born writer . . . What distinguishes Alston’s stories from the usual white American variety—derived from O. Henry at however far a remove—is that there’s no inevitable whip-crack ending. In fact, he makes his points by judicious ‘signifying’ . . . We see [his subject] clearly from the part of the retina that has not been fogged by too much direct staring.”

—Robert Graves

“Set mostly in North Carolina, moving to New York City and the German front, Anderson’s fifteen short stories are populated by African American outsiders, among them drifters, addicts and tricksters . . . Anderson’s writing is taut, the narrative voice beguiling . . . In an echo of his contemporary James Baldwin, Anderson picks apart the tired threads of racial politics . . . There’s an implicit ‘So What,’ to echo Miles Davis, in this fresh and unsettling collection.”

—Douglas Field, Times Literary Supplement

“The best books I’ve read in the past year are The Laws of Simplicity by John Maeda and Lover Man by Alston Anderson . . . Lover Man feels like an anthology, where it skips around but it all makes sense.”

—Michael Bennett, Financial Times

“The depth with which Lover Man explores Black life comes draped with a raunchy and sly critique as well, something rarely seen in major literature in the 1950s and ’60s . . . Anderson seemed to have little interest in either respectability or politics . . . The characters portrayed in Lover Man certainly exist outside of any culturally approved image. Anderson’s gritty portrayal of Black, Southern, country life stands as a testament to his talent.”

—Carr Harkrader, The Assembly

“These stories . . . display a genuine talent for fiction . . . All are rich with wonderful speech—racy, ribald, robust and startling . . . Some of these stories deal with death and violence and sorrow. One is about a rip-snorting fight with razors. Another is about the misery of a girl suffering from a bungled abortion and the baffled frustration of her lover. Several are about lust . . . they all are full of vigorous life, taut with emotion. They show that Alston Anderson possesses many of the qualities of a first-rate novelist—an ear for speech, a gift for storytelling, a sense of humor and a feeling for the humanness of human beings.”

—Orville Prescott, The New York Times (1959)

“With this series Anderson introduces himself not only as a first-class writer, but also as an observer who aims to talk only about life as it is lived by people who are not professionally sensitized to it . . . He is fascinated by the South, by what he has seen, and by what he has heard, and he manages to re-create that fascination for his reader.”

—TIME Magazine (1959)

“In spite of some strong themes, [these stories] are told with a rare delicacy, by what Mr. Anderson calls signifying rather than direct statement; they have no tricks and yet how clever they are . . . I do not remember a small book which has given me such a large experience.”

—Rumer Godden

“The [herald] of a new literary renaissance . . . [The] so-called bourgeoisie will regurgitate over Mr. Anderson’s stories. They'll want to say ‘’Taint so!’ But it is so, and the only reason the bourgeoisie will object is because Mr. Anderson has drawn our picture for everybody (including white folks; in fact, mostly white folks) to see. There’s the rub.”

—P. L. Prattis, Pittsburgh Courier (1959)

Pair your McNally Editions hat with a book! Choose from Ursula Parrott’s Ex-Wife, Gary Indiana’s Rent Boy, Grégoire Bouillier’s The Mystery Guest, Kay Dick’s They, Alston Anderson’s Lover Man, Djuna Barnes’ I Am Alien to Life, or Dorothy Parker’s Constant Reader, and get the hat that goes with it—for only $40.

Alston Anderson (1924–2008) was born in Panama to Jamaican parents who brought him to North Carolina as a child. After serving in the Army during World War II, Anderson attended North Carolina College and Columbia University on the G.I. Bill, as well as the Sorbonne, where he studied German philosophy. Moving in expatriate circles, he overlapped with James Baldwin at Yaddo, stayed with Robert Graves in Majorca, and co-interviewed Nelson Algren with Terry Southern for the Paris Review. After Lover Man, he published one novel, All God’s Children, a critical and commercial failure. Following a series of personal and professional ruptures, Anderson vanished from the public record in the early 1970s until the time of his death in New York’s Bellevue Hospital.

Kinohi Nishikawa is the author of Street Players: Black Pulp Fiction and the Making of a Literary Underground. He teaches African American print culture at Princeton University.

Lover Man • Paperback ISBN: 9781946022547

Feb 7, 2023 • McNALLY EDITIONS no. 14

5" x 8.5" • 208 pages • $18.00

eBook ISBN: 9781946022554

What type of reader are you? A realist, an escape artist, or a decadent? Find out by taking the McNally Editions reader quiz, which matches readers with a tailored subscription carefully curated to your tastes and sensibilities.

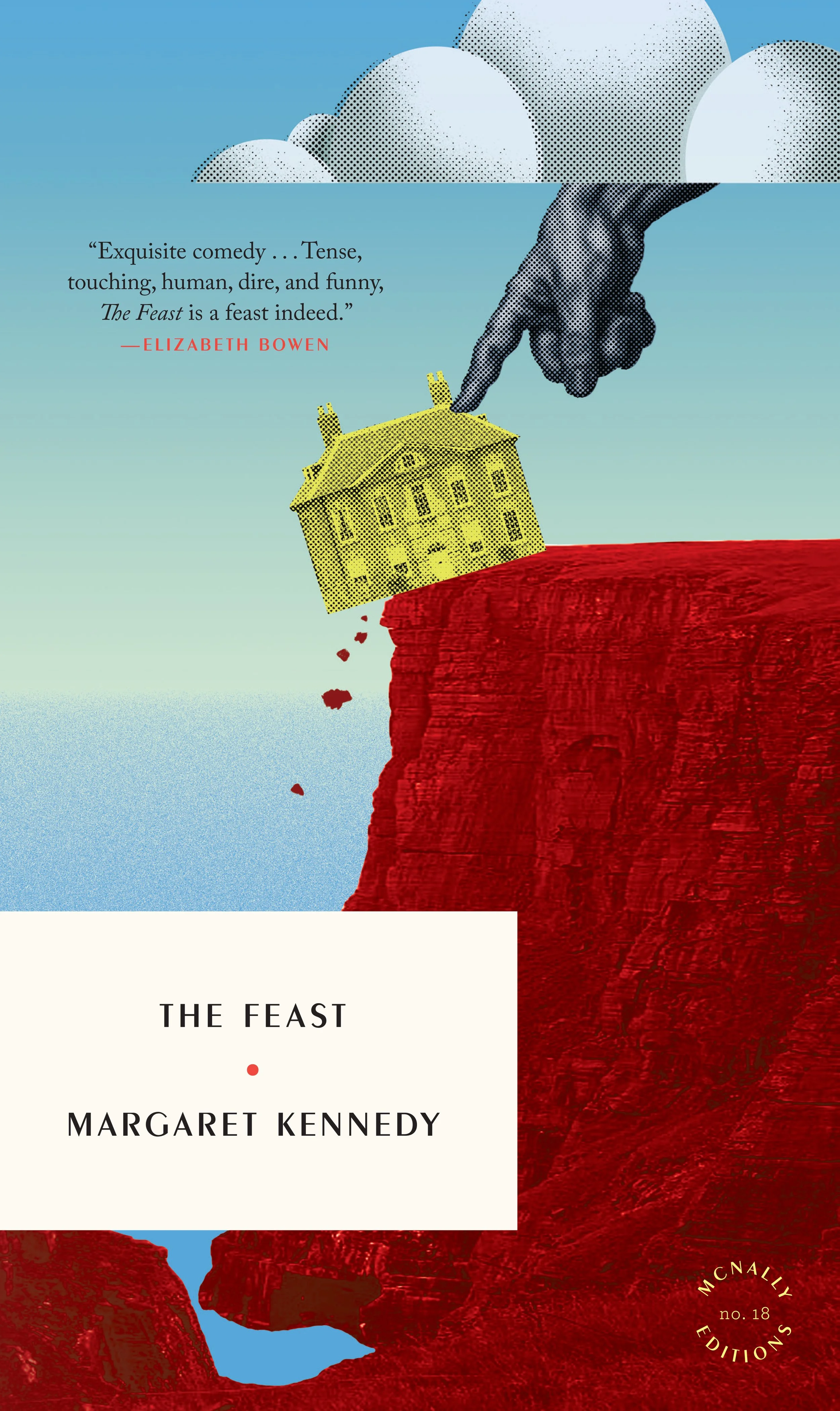

We’ve got recommendations galore for your reading list. First, hot off the press, is ‘The Feast,’ Margaret Kennedy’s ingenious upstairs-downstairs comedy which reads like ‘White Lotus’ time-machined to 1940s Cornwall.

“There’s a growing band of people digging through library stacks and second-hand bookshops in search of lost classics. I’m one of them.“